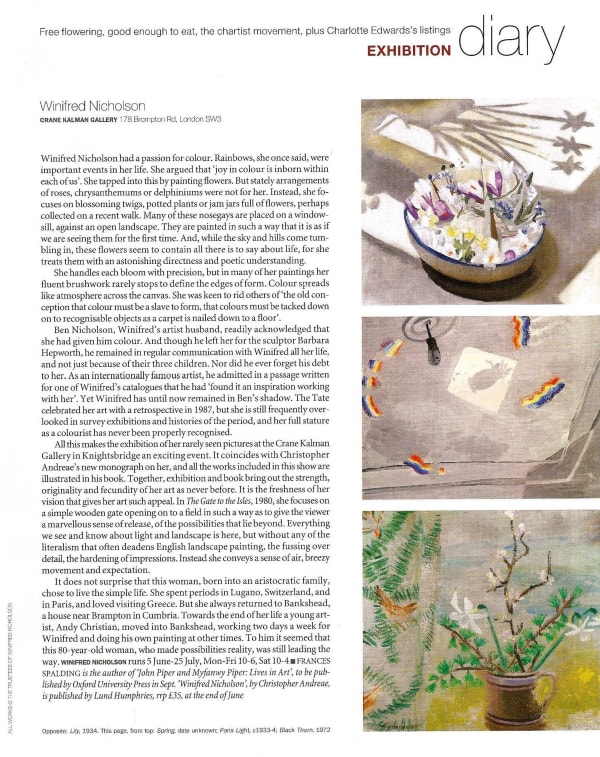

Winifred Nicholson had a passion for colour. Rainbows, she once said, were important events in her life. She argued that 'joy in colour is inborn within each of us'. She tapped into this by painting flowers. But stately arrangements of roses, chrysanthemums or delphiniums were not for her. Instead, she focuses on blossoming twigs, potted plants or jam jars full of flowers, perhaps collected on a recent walk. Many of these mosegays are placed on a windowsill, against an open landscape. They are painting in such a way that it is as if we are seeing them for the first time. And, while the sky and hills come tumbling in, these flowers seem to contain all there is to say about like, for she treats them with an astonishing directness and poetic understanding.

She handles each bloom with precision, but in many of her paintings her fluent brushwork rarely stops to define the edges of form. Colour spreads like atmosphere across the canvas. She was keen to rid others of 'the old conception that colour must be a slave to form, that colours must be tacked down on to recognisable objects as a carpet is nailed down to a floor'.

Ben Nicholson, Winifred's artist husband, readily acknowledged that she had given him colour. And although he left her for the sculptor Barbara Hepworth, he remained in regular communication with Winifred all her life, and not just because of their three children. Nor did he ever forget his debt to her. As an internationally famous artist, he admitted in a passage written for one of Winifred's catalogues that he had 'found it an inspiration working with her'. Yet Winifred's has until now remained in Ben's shadow. The Tate celebrated her art with a retrospective in 1987, but she is still frequently overlooked in survey exhibitions and histories of the period, and her full stature as a colourist has never been properly recognised.

All this makes the exhibition of her rarely seen pictures at the Crane Kalman Gallery in Knightsbridge an exciting event. It coincides with Christopher Andreae's new monograph on her, and all the works included in this show are illustrated in his book. Together, exhibition and book bring out the strength, originality and fecundity of her art as never before. It is the freshness of her vision that gives her art such appeal. In 'The Gate to the Isles', 1980, she focuses on a simple wooden gate opening on to a field in such a way as to give the viewer a marvellous sense of release, of the possibilities that lie beyond. Everything we see and know about light and landscape is here, but without any of the literalism that often deadens English landscape painting, the fussing over detail, the hardening of impressions. Instead she conveys a sense of air, breezy movement and expectation.

Is does not surprise that this woman, born into a aristocratic family, chose to live a simple life. She spent periods in Lugano, Switzerland, and in Paris, and loved seeing Greece. But she always returned to Bankshead, a house near Brampton in Cumbria. Towards the end of her life a young artist, Andy Christian, moved into Bankshead, working two days a week for Winifred and doing his own painting at other times. To him it seemed that this 80-year-old woman, who made possibilities reality, was still leading the way.

Winifred Nicholson runs 5th June - 25 July.

Frances Spalding

Published in The World of Interiors, 2009. © The Condé Nast Publications Ltd